Ubi bene ibi Colonia is a term with unknown roots and is a derivation of a quote by Cicero (Patria est, ubicumque est bene). Its modern translation “The place that is beautiful is Cologne” (or rather “Cologne is where the heart is”) is a version of the idiom “Home is where the heart is,” and expresses the immense pride that the citizens of Cologne have for their city. It has become part of the colloquial language in Cologne and can be found on souvenir items such as T-shirts, mugs and stickers. I have chosen this motto, as it best describes the topic of this article, which focuses on one particular aspect of my PhD thesis entitled “Religion, Identity and the Public Sphere in 16th Century Cologne,” namely identity formation through representations of the city. In this study, I provide a small glimpse into the history of the cartography of Cologne, in particular the 16th Century, because it was this century that was pivotal in the development of maps, changing the representation of this city from a religious centre to one based on power and trade.

1500

Take a walk with me. Imagine we are walking through the streets of Cologne in Germany at the beginning of the sixteenth Century. Our starting point is just inside the city walls that protect it from possible attacks. Let us walk towards the river. We walk past churches, monasteries, houses, and the half-built cathedral with its wooden crane on its south tower. The building site of this cathedral is not busy. There is little money to finance the building, so only a handful workers are around. In a few years, work on this great gothic cathedral will cease altogether and not continue until the 19th Century. We continue our city tour and walk through small cobbled alleyways and across market squares. It is a busy city, and the streets are teeming with life. We pass all sorts of people: beggars, richly dressed merchants, peasants, nuns, monks, messengers on foot, a few noblemen on horseback and hand-drawn carts.

We hear different noises drifting to us from various corners of this part of the city: hammering and sawing, people on the markets crying their wares. The stench in the air is almost tangible: the smell of fish, the unmistakeable odour from the tanneries, and of course the stench from the alleys- there are no underground sewers. Everywhere we look, people are conducting their business. The churches we pass are also busy. There are quite a few of them. Many people are attending mass and praying, for this is also a very pious city. After all, the relics of the Three Wise Men are housed in the large cathedral we passed earlier. We continue onwards and then we finally reach our destination.

We have reached the banks of the river Rhine. It is busy here too. There are ships moored at the harbour, boxes being loaded and unloaded, workers repairing rigging, merchants directing their goods, and a good many small barges are on the river too. Some are crossing over to the other side, towards Deutz, the small town just across from Cologne. The bridge that had existed here in Roman times has never been rebuilt, so there is no other way of crossing the river. If we look to the left or to the right, we can see watchtowers in the distance, guarding the city from unwanted intruders. But let me tell you a secret: I am a local, so I know my way around here. I know how to find my way through this maze of alleys, know shortcuts, places of interest and what areas to avoid. I wish I could give you a map of the city, but it is the beginning of the 16th Century, and street maps have not yet been invented for Cologne.

1531

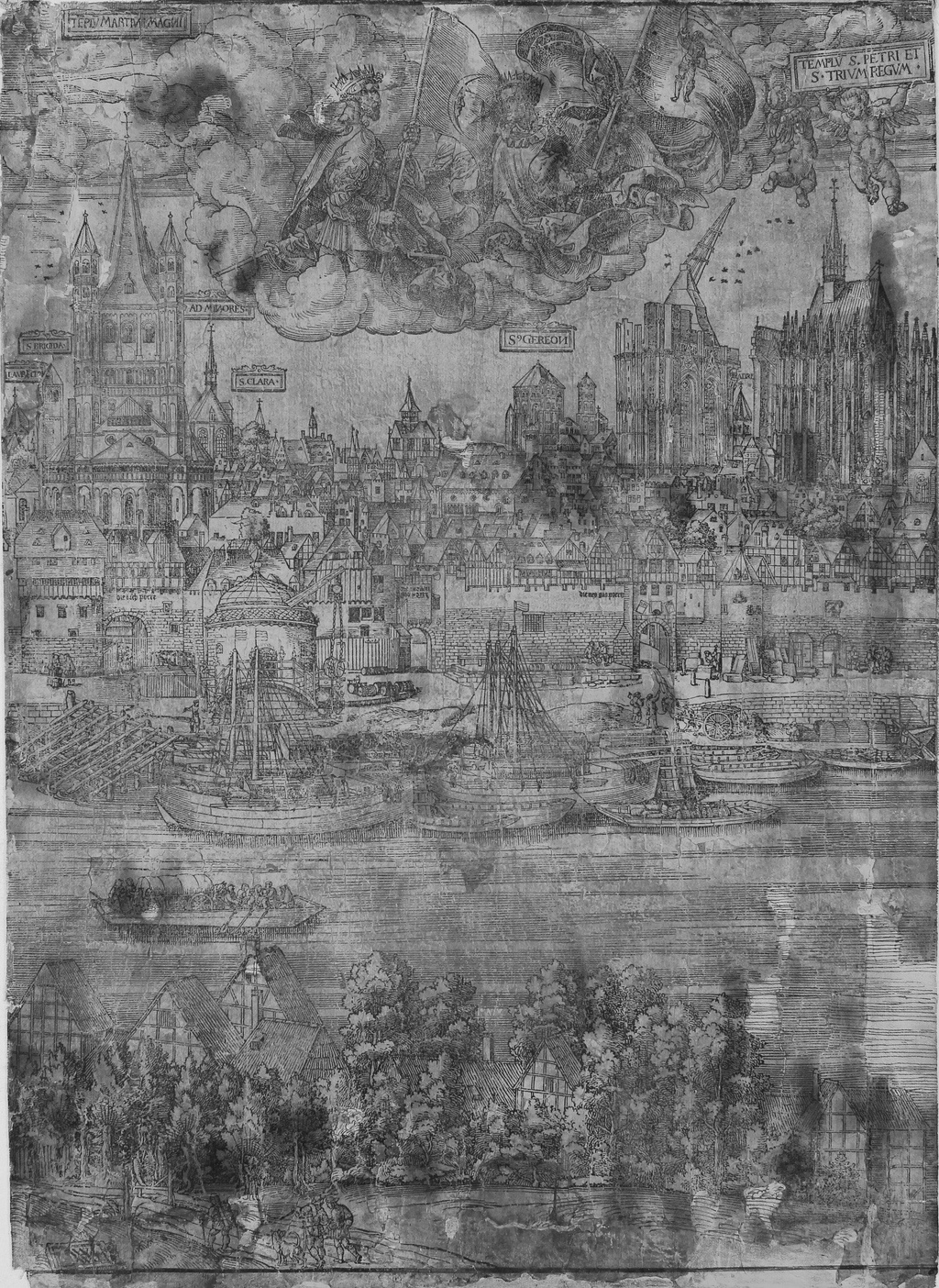

So let us fast-forward a few years. It is the year 1531, and the first cityscape of Cologne has been produced by Anton Woensam, a skilled German engraver. It is called Die große Kölnansicht (The great view of Cologne) and is a coronation gift from the city to Ferdinand I, shortly to be crowned king, brother to the then reigning Emperor Charles V. It is made up of nine woodpanels, and its detail and splendour are overwhelming. What is presented to us here is a cityscape that captures the spirit of the city. Its piety is illustrated by the portrayal of no less than 40 churches, meticulously detailed and labeled. The city needs to defend its strong Catholic position, as Martin Luther and his Reformation movement have created unrest in many different cities in the Holy Roman Empire. Cologne wished to underline its unwavering alliance to the Church and especially to Emperor Charles V, as he was the one who had Martin Luther outlawed in 1521.

The portrayal of the city’s activity is just as significant. Certainly noteworthy are the great number of trade ships on the river, as well as the docks which show the multitude of merchandise and skilled workers going about their daily business. Completing the cityscape are the city gates and the secular buildings. The city gates imply that the city is well fortified, and capable of defending its territory. The secular buildings highlight the presence of guilds and burghers in Cologne, and also illustrate the city’s importance as an international trading post. Its prime location on the river Rhine linked the Alpine Region to the Lower Countries, facilitating the movement of many different products, including paper that was in high demand for the printing of books and leaflets. In the 16th Century, Cologne was already one of the five leading print centres in Europe.

Yet this cityscape is still not a street map useful for navigating through the city. Although beautiful, its perspective is not helpful. What we need is a different perspective, one from above, which is also known as the bird’s-eye or oblique view where we can see the proper layout of Cologne. So we need to jump ahead a few years again.

1568

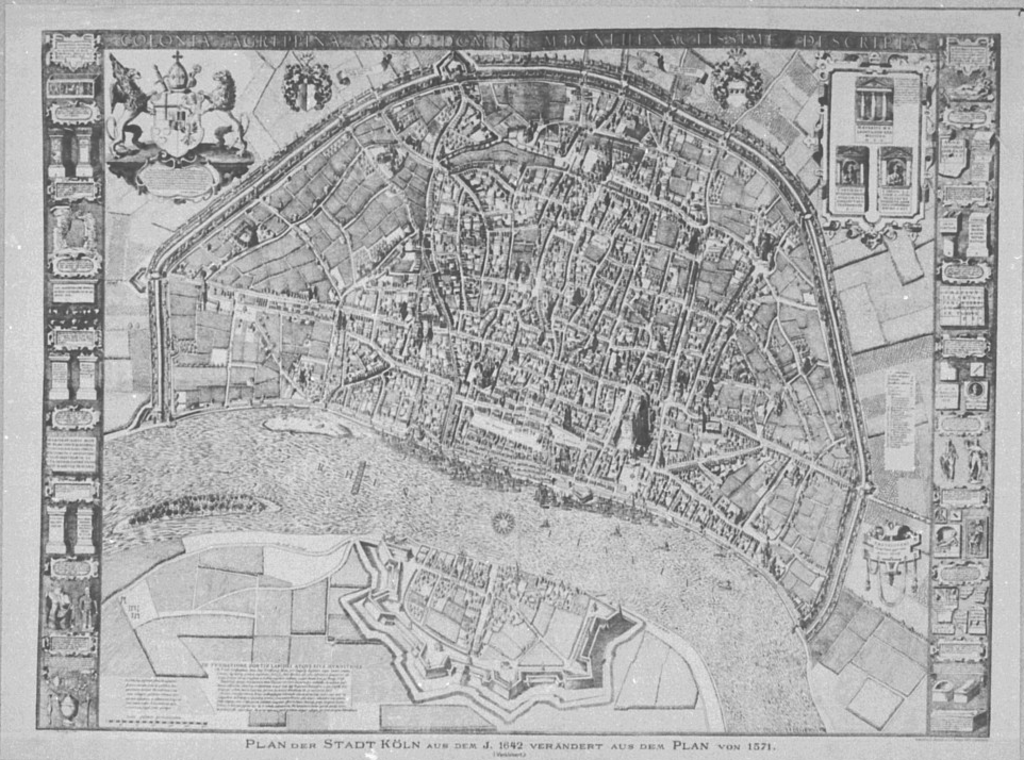

It is 1568 and Arnold Mercator, son of the famous Gerhard Mercator who invented the Mercator projection (a system of rhomb lines on a world map which facilitated ships to hold a constant course) produced the first accurate map of Cologne. It was commissioned by the city council in 1568, which not only wished for a realistic representation of the city, but also required a street map for a planned inspection of weapons in all households. Recent religious persecution in parts of the Lower Countries and other cities in the Holy Roman Empire had led to a large increase in immigrants, a fact the council was not comfortable with, as it feared that the surge of Protestants would destabilize the peaceful city which stayed Catholic in spite of several Reformation attempts.

The oblique perspective of this map allows the viewer to recognise the detailed buildings, of which places of interest, such as the city hall and the cathedral, are clearly identifiable. Note the construction crane on the south tower. Work on the cathedral has ceased, and the crane will become one of the prominent features of the city (and every representation of the city) until the 19th Century. Emphasis has also been laid on the different entrances into the city, underlining the land routes, as well as the access to the river, thus signifying the city’s prime location for trade, and showing the city’s strong fortifications. Here, again, we are able to see the richness of the city, including the use of agricultural land within the city walls. It is through maps like these that Cologne was able to assert its important presence within the European realm, as it was the largest city in the Holy Roman Empire and could compete in trade, power and prestige with cities such as London and Paris.

Thus ends our little excursion into 16th Century Cologne and the beginnings of city maps. Even though there is a vast amount of images of the city, representations of the city in the 16th Century is an area of Cologne’s history that has yet to be studied in detail. While maps of Cologne of this particular period have been treated individually, they have not been studied in the specific context of identity formation. The images I have used in this study are particularly important in my research as they were seminal to the further development of maps and cityscapes of Cologne and ultimately shaped the relationship the citizens of Cologne forged with their city. It is, perhaps, not surprising, that the citizens of Cologne use the term with pride: Ubi bene ibi Colonia.

A special thank you to my supervisor Professor Brendan Dooley. I am a second year PhD student in the programme ‘Texts, Contexts, and Cultures.’ Thank you to the Wallraf Richartz Museum for permission to use the detail of the Woensam Stadtansicht. Thank you to the Rheinisches Bildarchiv for permission to use the Mercator map.