Unix is a computer operating system. Strictly speaking, ‘Unix’ refers only to systems produced under license from the descendants of Bell Systems or Berkeley University, but there are so many derivatives both free and commercial, that it's simpler to use ‘Unix’ to mean all of them, because they all work alike and often look alike.

In this document, ‘Unix’ is therefore [ab]used to include SunOS, HP/UX, Digital Unix, GNU/Linux, and Apple Macintosh OS X.

For most work, people use a graphical user interface (the X Window System or similar). However, there are some tasks for which typed commands are faster and more powerful, particularly when you need to bulk-manage groups of files or manipulate data in formats not provided for by your windowing system. If you need to manage files and folders on a server or other remote system (elsewhere on the Internet) to which you have login access, but no windowing facilities, then typed commands are your only way.

When you are logged into a Unix system, you get a chat-like interface where you can type your instructions to the computer and it will respond with results.

The computer signals its readiness to accept a new command by displaying a dollar sign ($), sometimes preceded by your username or current directory.

When you have typed a command, you must press the ↩ key after each command, otherwise nothing will happen. This is also referred to as the Enter, Return, or Newline key.

Remember you must press the ↩ key after each command, just like a chat system. Until you do so, the computer doesn't know you have typed anything, so nothing will happen.

Unix commands consist of a command name followed by options and arguments, as shown in the examples in Table 1 below.

| Type | Command | Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| Command with no options or arguments | top | display the list of most active processes running |

| Another command with no options or arguments | passwd | change my password (it will ask for it twice) |

| Command with one option | ls -l | list all file details in ‘long’ format |

| Command with one option and one argument | ls -l thesis.pdf | list details about a specific file |

| Command with just one argument | rm thesis.tmp | remove the specified file |

| Command with an option (-O) with its own argument (newinfo.dat) as well as an argument for the command itself (the URI) |

|

download data from a website straight into a named file |

| Command with three combined options | ls -laR | list all files, even hidden files, and including all files in subdirectories |

| Command with an option and multiple arguments | cp -i thesis.* /var/backup/ | copy all thesis files to a backup directory but ask me before overwriting anthing |

You can only do things to files and directories that you own: if they're not yours, leave them alone (or contact the system manager if you think you ought to have access).

Like all modern computers, Unix, GNU/Linux, Apple Mac OS X, and Microsoft Windows all use a hierarchical file system (see Figure 1 below) like an inverted family tree, with the root (starting-point) at the top. The only major difference is that Microsoft Windows has multiple roots, one for each disk (called C:, D:, E:, etc), whereas all other systems only have one root (called ‘/’).

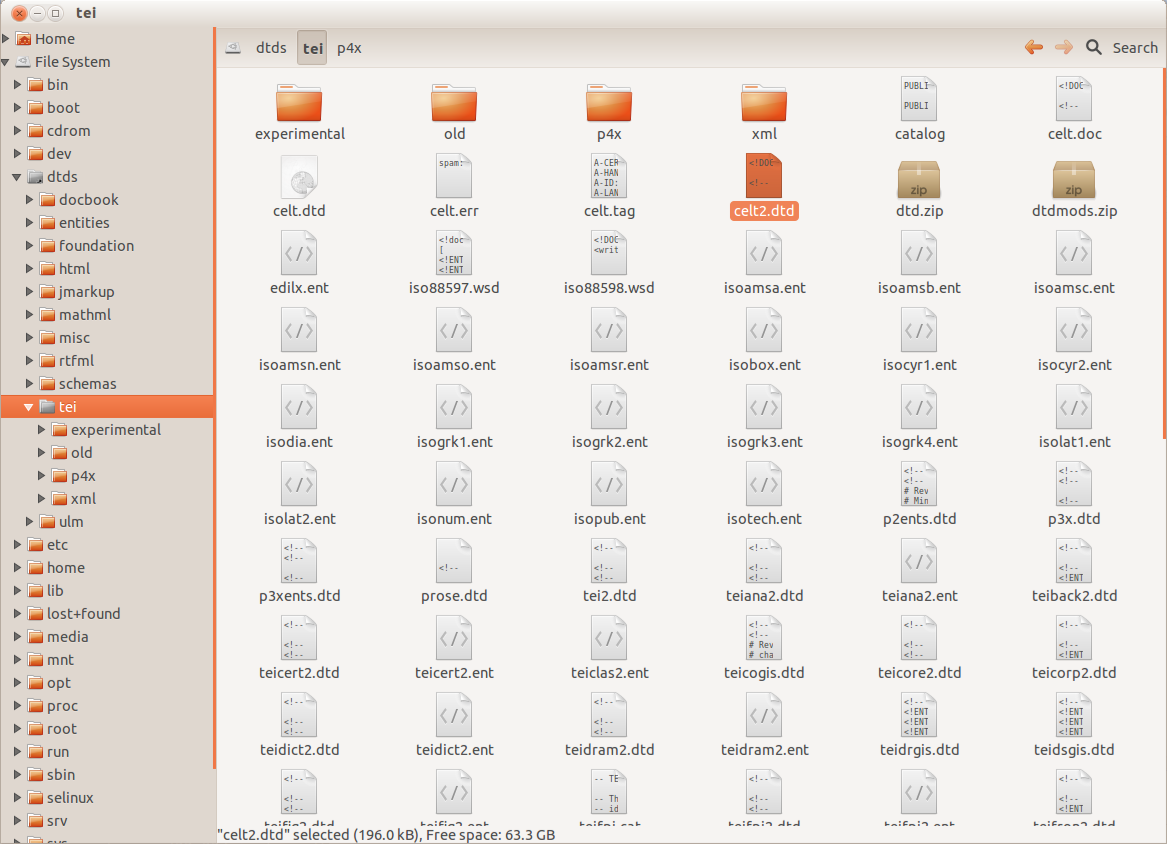

A typical directory-and-file browser, Note the ‘family-tree’ type display of the directories and their subdirectories at the left-hand side.

At any one time, you are ‘in’ a particular directory, referred to as your current working directory. When you log in, you are put into your account's home directory. If your username is jean then your home directory would typically be /home/jean or /usr/users/j/jean or something similar depending on the type of machine and how it is set up. You can show your current working directory with the pwd command, and you can change into any directory to which you are permitted access with the cd command.

Using Figure 1 above as a graphical example, you are in /dtds/tei; that is, starting with the root of the file system (/), your location is in the dtds directory, and in the tei subdirectory of that. To get there from your home directory, you would type cd /dtds/tei ↩. This is an absolute reference, because it works from anywhere on the system, and always goes to the same place.

Within this directory, however, you would refer to any of the four subdirectories of the current working directory simply by name; for example cd p4x ↩. These are called relative references, because they relate only to the directory you are in when you use them. You could type cd /dtds/tei/p4x but there would be little point if you're already in the /dtds/tei directory.

Keep up to date with our RSS newsfeed Keep up to date with our RSS newsfeed |

Electronic Publishing Unit • 2008-11-19 • (other) |